Advertisement

Advertisement

Shut that door and keep the heat in—it's a familiar cry in winter; in summertime, you're more likely to see people closing doors and windows to keep the heat out and save on the air-conditioning. How can you have an airtight, energy efficient home that's also healthy and well-ventilated? Heat recovery ventilation (HRV) and energy recovery ventilation (ERV) offer a solution, bringing fresh air into your home without letting the heat escape. Let's take a closer look at how they work!

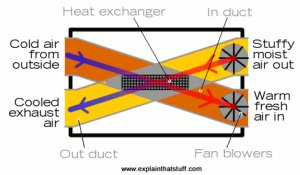

Photo: The inside of a typical heat recovery ventilation (HRV) system. You can see the blue and red air ducts on the left, the diamond-shaped heat exchanger in the middle, and the air blowers on the right. HRV systems are made by many different companies, including Broan, Fantech, Honeywell, Vaillant recovAIR, Renewaire, and Venmar. Photo courtesy of IBACOS and US DOE/NREL (Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory).

What's the problem?

What's the problem?

Modern homes are usually built to far higher technical standards than buildings constructed a few decades ago and are much more energy efficient, largely thanks to better heat insulation. One key area of improvement has been to make buildings more airtight so they hold onto the heat we put into them for longer. But there's a drawback: our homes need regular changes of air to keep them healthy. Baths and showers, doing the dishes, clothes washing machines, drying clothes indoors, and even simple breathing produce astonishing amounts of water inside our homes: according to leading ventilation manufacturer Vaillant, a typical family will produce 10–15 liters (3–4 gallons) of moisture each day! Let that problem go unchecked and you'll get problems like mold and mildew, dust mites and a greater risk of asthma. Opening doors and windows is the obvious way to get rid of moisture and bring in fresh air, but if you do that in winter you might just as well flush your money down the toilet: all the heat you've expensively introduced into your home will blow away in the breeze. An old drafty house solves this problem by being automatically well ventilated, but it's probably also freezing cold because it's useless at holding onto heat; a modern energy-efficient home solves the draft problem but may be stuffy and underventilated. So what to do?

Nature's answer

Nature's answer

Let's look to nature, which solved this problem some time ago. Our bodies are a bit like our homes inasmuch as they need regular supplies of fresh air and have constant clouds of damp, "stuffy" air to get rid of. How do they do it? With an ingenious invention called the nose! As a child, you might have learned that it's better to breathe through your nose than through your mouth because your nose warms and filters incoming air. What your nose actually does is called heat exchange: it lets cool incoming air flow very close to warm outgoing air so heat energy is transferred between the two instead of being lost. As a result, the air you breathe in is warmer and the air you breathe out is cooler—and (among other things) that helps your body to retain heat energy.

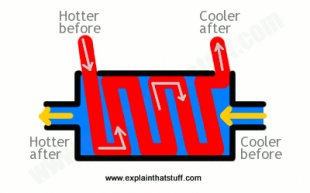

Photo: The basic principle of a heat exchanger: a hot, outgoing fluid (red) flows past a colder, incoming fluid (blue). Without them actually mixing together, the hot fluid gives up most of its heat to the cold fluid.

What is heat recovery ventilation?

HRVs are essentially noses on houses: they consist of two ventilation ducts running next to one another passing between the inside and the outside of a house. One carries cool, fresh air in; the other carries moist, stale air out. The clever bit is that the airstreams run through a device called a heat exchanger that allows the outgoing air to pass most of its heat to the incoming air without the two airstreams actually mixing together (read how this works in our article on heat exchangers). Usually there's a fan (blower) in each duct that can be turned up or down either manually or automatically depending on the temperature and humidity levels. The incoming air supply may also have a bypass fitted to it so that on summer days when it's cooler outside than in, cold outside air can be channeled straight into the home without meeting outgoing air (much like opening a sash window).

Artworks: Left: How an HRV works (simplified): The hot, moist waste air from the home (passing down the yellow duct) gives up virtually all its heat as it passes through the heat exchanger on its way out of the building. The cold, dry incoming air (flowing through the brown duct) picks this heat up as it flows in. Ideally, no heat is lost. Since the incoming and outgoing air flow past in opposite directions, this approach is known as a counterflow.