Josh, a builder in Columbus, Ohio, has been hired to add a bathroom in the attic of an existing house. Although he had hoped to use cellulose insulationThermal insulation made from recycled newspaper or other wastepaper; often treated with borates for fire and insect protection. in exterior walls, the homeowner's budget allowed fiberglass batts. Josh was counting on the kraft paper facing on the insulation to serve as a vapor retarder, but to his surprise the building inspector insists the paper be removed before the insulation is installed.

What gives? And will the inspector's decision increase the risk of moisture problems in the bathroom, surely one of the most humid rooms in the house?

The Q&A discussion actually provided some support for the misunderstood inspector, as well as a look at materials and building techniques that will keep moisture problems at bay.

Will water vapor rot the walls?

Between tub and shower, sinks and toilet, a bathroom has a high potential for water damage, not only from leaks of liquid water but also from water vapor that can collect inside exterior walls and condense. Vapor retarders are there to slow the diffusion of moisture, so the building inspector is off base, argues senior editor Martin Holladay.

Even so, Holladay adds, vapor diffusionMovement of water vapor through a material; water vapor can diffuse through even solid materials if the permeability is high enough. is rarely as big a problem as we might think. If the inspector's ruling underscores an "incomplete understanding of building science, " it's probably not going to have a serious practical effect. This is one battle that's probably not worth fighting.

Robert Riversong isn't so sure the inspector is wrong. Paper facings on conventional gypsum drywall provides food for mold. Riversong notes that the tiled portion of the wall will include a Schluter-Kerdi waterproofing membrane, so removing the kraft paper may have a double benefit: reducing the chances for trapped moisture by having one rather than two vapor retarders, and removing the paper that encourages mold growth.

"At least this inspector is on the right track, " he says.

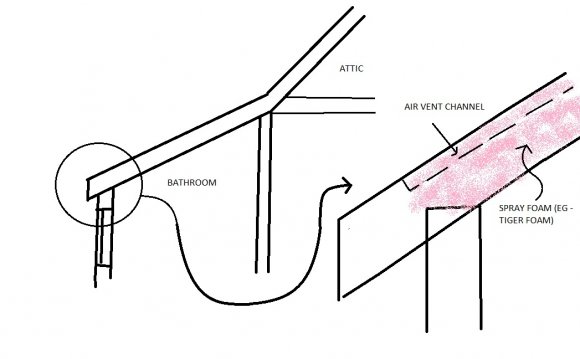

One problem, however, is installers used 14 1/2-in. batts instead of 15-in. wide friction-fit batts. When the paper layer is removed, it creates a higher potential for air leaks between the framing and the batts, and air leaks are capable of carrying larger amounts of moisture into wall cavities than vapor diffusion.

To control bathroom moisture, use a fan and waterproofing membrane

There are really two kinds of water to worry about: the water vapor that diffuses into the wall, and the bulk water that comes from leaks, careless bathers, splashes from the sink and around the toilet.

One way of controlling water vapor is to get humid air out of the bathroom before it can do any damage. A bathroom fan will take care of that. Humidistats, which measure humidity levels and turn the fan on accordingly, as well as more basic timers, are frequent suggestions for making sure the fan runs long enough to do its job.

Riversong finds humidistats unreliable and recommends a switch from Energy Federation that incorporates a programmable delay for the fan. When the switch is turned off, the bathroom light goes out but the fan continues to run for up to 60 minutes. No one has to remember to use a timer because the fan operates automatically.

Modern building materials will help prevent damage from liquid water. Josh was planning to use Schluter-Kerdi waterpoof membrane under ceramic tile, as well as DensArmor Plus drywall. DensArmor, made by Georgia-Pacific, is a paperless wallboard highly resistant to mold. It incorporates fiberglass mats on the front and back of the panels instead of paper, eliminating mold supporting cellulose.

ADKJAC, who specializes in bathroom construction and repairs, finds most problems occur on lower areas of wetted tile, wetted joints in corners and around the tub, and in the floor around the toilet. He's a big fan of both Schluter and DensArmor products. Combined with a coat of primer and two topcoats of latex paint, they are enough for a "perfect job."

Finally, sealing the tile grout can't hurt. Riversong recommends siloxane or silane rather than silicone.

Bottom line: Vapor diffusion and bulk water are separate issues, each of which must be addressed. As a practical matter, the removal of the vapor retarding paper layer on the fiberglass insulation shouldn't be a huge problem. A bathroom fan with a timer and/or a humidistat should be enough to keep humidity levels down. As to bulk water, paperless drywall and a waterproofing membrane beneath the tile should do the trick.

Is kraft facing in a bathroom against the building code?

The undercurrent running through the discussion is the role the inspector played. Josh decided there wasn't much point in arguing with him about removing the insulation's paper layer. Instead, he planned to develop some seminars for homeowners and would make sure the building inspector got his own invitation.

Was the inspector justified? Holladay doesn't think so. He suggests the key question is, Which part of the code calls for the removal of a kraft paper facing from insulation installed in bathroom walls? Without a specific provision in the code, he adds, the inspector "lacks the authority" to insist the paper be removed.

Hang on, replies Riversong. The International Residential Code gives inspectors wide latitude as long as they conform to the "intent and purpose of the code."

That may be true, answers another poster, but the inspector has to start with some specific rules on bathroom insulation. He can't interpret something that doesn't exist. Further, many calls by inspectors have been overruled as arbitrary when challenged by homeowners or contractors.

In the end, any local inspector on site has a great deal of discretion. Well-intended rulings that flout up-to-date building science are probably more frequent than builders would like to see. But at the very least, these decisions often ignite a discussion that helps educate everyone.